An unlikely coalition’s multi-year successful effort in search of just one signature.

With full ceremonial honors in view of the entire national and international communities, President James Earl Carter, Jr. was eulogized in a religious service at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC on January 9, 2025. His record as a family man, religious servant, public figure and international peace maker was recounted proudly by many speakers. He was honored not just for his public life, including being President, but for his decades of later work pursuing peace internationally and building homes nationally for ordinary working people through Habitat for Humanity. For the life he lived and what he gave, he was deserving of all those heartfelt commendations. However, the US cooperative community had its own special gratitude.

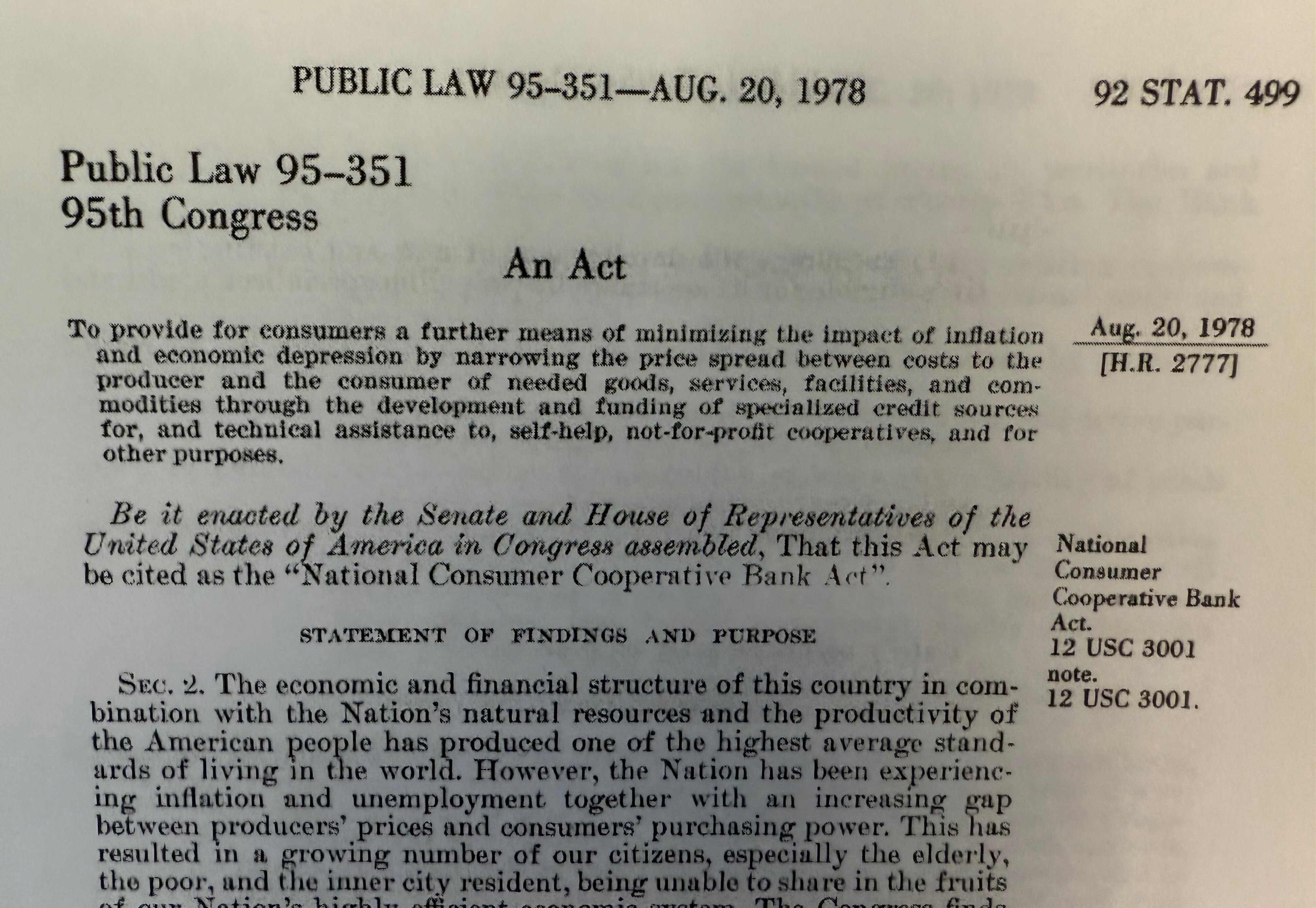

With his signature on August 20, 1978, President Carter brought into law the creation of today’s National Cooperative Bank (NCB). Two days later, the White House hastily hosted a reception for the bank’s disparate coalition of supporters. Among those represented were Republicans and Democrats, as well as a smattering of Nader’s Raiders, libertarians, consumer and agricultural co-op members, credit union leaders, CEOs of Fortune 500 cooperatives, and other co-op organizations. Many different people and entities turned up to celebrate a most unusual victory which earned them the national bank they needed.

A very unique institution was in the making whose users had quite a story to tell. Though the bank’s supporters were committed, they did not have the political strength or the organizational resources of most backers of national legislation. More importantly, the opponents of the bank were many with well-funded, competent lobbying entities.

What is memorable about the signing of the bank’s legislation is the many seemingly insurmountable barriers the bank’s supporters had to overcome on their path to victory. Most professional lobbying powers would have dropped this type of campaign before it even started. Yet, the mostly amateur backbone supporters of the bank in their first ever and perhaps only congressional campaign were oblivious to the reality of the “Hill”and knew they were there only to win.

The concept was valid and worthy and the gain was for ordinary Americans who wanted to work together to create and strengthen their cooperative enterprises. No single person or entity would become rich from the passage of the bank’s legislation, however, the nation would have one more valuable tool to create economic gain for the non-agricultural, cooperatively-owned enterprises and their members. A neglected corner of American enterprise would finally be given a fair shake at building and achieving the American dream.

“In addition, special credit should be given to the thousands of individuals and cooperatives and other organizations without whose efforts and support there would be no bank.”

Forward: Where Credit Was Due. 1985, Cooperative Foundation, St, Paul Minnesota

The journey of the bank’s legislation to gain congressional passage and the President’s signature, however, was not an easy one. Normally, the ever-churning congressional machinery would quickly kill such an idea.

Many people point to October, 1974 as the beginning of the concept of the National Cooperative Bank. That year, the Cooperative League of the USA (CLUSA) (now the National Consumer Cooperative Business Association – NCBA/CLUSA) held its bi-annual Congress in San Francisco, California.

The key topic of the 1974 multi-day meeting was that consumer cooperatives of all kinds were in a growth spurt but did not have the cooperative financing structure in place that the agricultural co-op members of CLUSA had.

The Chair of CLUSA, Frank Sollars, was also Chair of Nationwide Insurance which was created by Ohio’s agricultural cooperatives. As time went by, he and Don Rothenberg, Education Director of the Berkeley Co-op, became the unlikely co-partners and co-pilots of this multi-co-op crewed ship.

During the CLUSA Congress, the three consumer cooperatives in the Bay area, the Berkeley Co-op, the Palo Alto Co-op and Associated Cooperatives (a wholesale co-op owned by 10 California consumer cooperatives), hosted nine dinners throughout the Bay Area which brought together by plan the leaders of both agricultural and consumer cooperatives to discuss the concept of consumer cooperatives having their own national bank similar to that of the Farm Credit System.

These meetings generated an excitement that spread back to the sitting CLUSA Congress and bought about a commitment by the CLUSA board to sponsor the concept of a bank for consumer owned cooperatives. At the CLUSA Congress, CLUSA appointed chairs and co-chairs of a Bank Implementation Committee (BIC) tasked with taking the burgeoning concept from inception to completion in the US Congress.

The National Cooperative Bank effort began during the Ford Presidency but some initial actions which signaled an early ominous defeat delayed the process into the Carter presidency. The staff of the incoming Carter administration was at first non-committal and occasionally negative about the creation of the bank. In fact, Treasury staff took the lead in opposing the immediate creation of the bank. Instead, Treasury staff introduced legislation for a pilot study which was code in DC for “Let’s kill this idea quietly.”

Seeing this tactic, bank supporters now led by new CLUSA President, Stanley Dreyer, hurriedly set in motion a congressional strategy to oppose Treasury’s study (but not President Carter). The bank study bill (instead of the bank bill) was brought to the House floor on a voice vote in which the presiding chair of the House (that day an anti-bank supporter) declared the ayes have it, meaning the bank concept was simply gone and replaced with the bank study.

Fortunately, Chalmers Wylie (R-OH), a bank supporter and close friend of Frank Sollars, was on watch for any mischief and moved successfully for a record vote. The roll, when called, showed 228 nays v 170 ayes, a 58-vote margin. That one heroic parliamentary procedure by Wylie kept the bank alive rather than kill it.

The vote on the bank bill (HR 2777) came up soon thereafter and the outcome still appeared ominous. The votes were so close that the bank’s congressional champions kept the vote open to allow them to continue to fiercely lobby a few recalcitrant members to change their votes from nay to aye. The final vote was 199-198. After the vote, scores of member of congress claimed their changed vote had won the day. A story (confirmed later) was told of an avid co-op supporter corralling an opposing congress member in a House restroom and not letting him out unless he changed his vote.

The legislation then moved to the Senate where co-op supporters were equally unsure of the outcome. However, there were a few unique anomalies that played a positive role. Senator S. I Hayakawa (R-CA) had been elected for his banning student protest and arresting 400 students while interim Chancellor of San Francisco State. He served on the Senate Banking Committee and was seen upfront as a clear no vote. However, it turned out that while at the University of Chicago in Illinois, Hayakawa had served on the board of the Hyde Park Co-op and Central States Co-op. After moving to California, his wife Margedant was elected to the board of the Berkeley Co-op.

When the sub-committee of the Senate Banking Committee held its hearing on the bank, the California co-chairs of the BIC implored Dreyer and CLUSA staff to send notes every ten minutes to Hayakawa. That way the Senate pages would constantly nudge Hayakawa out of the narcolepsy he suffered from. It worked and Hayakawa’s strong sub-committee testimony brought other Republican Senators to support the bank.

At the sub-committee’s hearings on the bank in January of 1978, Treasury’s staff announced that after their own review, the Carter administration had enthusiastically agreed, there now was a need for a bank for consumer cooperatives. The change came about mainly because the massively successful efforts to stop the study had shown the administration that that groundswell of grass roots support was relentless and would not be denied.

Seeing the tenacity of support for the bank, the Carter administration changed their position to a solid “Yes”. The relentless three-year flood of phone calls and countless congressional visits and the unleashing of support letters had swayed the day. President Carter had added up all the positives and found that the co-op bank fit his core beliefs.

Behind the scenes other people were having an effect upon President Carter.

Senator Mondale (D-MN) had also served on the Senate Banking Committee and was a strong supporter of the bank prior to becoming Vice President under Carter. Minnesota’s co-op bank supporters kept reminding Mondale to use his voice to maintain his support. Behind closed doors at the White House, Mondale played a key role in getting Carter to make known his favor of the bank bill.

President Carter from Plains in Sumter County, Georgia was also reminded by neighbors in his own Georgia backyard that the bank was a worthy idea with lots of potential in his own state. Among those co-op bank supporters were Andrew Young (who Carter appointed as Ambassador to the United Nations and was a Eulogist at Carter’s funeral), John Lewis (who Carter appointed as associate director of ACTION who then later came to work for the NCB) and the indefatigable Ralph Paige, Executive Director of the Southern Federation of Cooperatives.

For decades, Carter was impacted spiritually by Koinonia Farms, (an inter-racial cooperative community just ten miles away from Plains in nearby Americus, Sumter County. Founded by Clarence Jordan in 1942, Koinonia Farms then went on to attract Millard and Lilian Fuller to start a program of home building for the poor of Sumter County. Upon returning from missionary service doing the same in Africa, the Fullers borrowed the Koinonia Farms housing program and turned it into Habitat for Humanity. Former President Carter was mentored in cooperation and self-help by Jordan and the Fullers and became Habitat’s most well-known volunteer.

Carter had his own examples of local cooperative self-help enterprises to turn to. The Carter family farm was a member of a peanut co-op, a rural electric co-op (his father became an early director of the Sumter Electric Membership Co-op) and a borrower from the Farm Credit System.

When the Senate vote was taken on July 13, 1978, it was 60 in favor and 33 opposed. It was the bank’s destiny to arise during the Carter administration. As it was Carter’s destiny on August 20th, 1978, to proudly sign the National Cooperative Bank into law. President Carter, we thank you for the help you gave us.

© David J. Thompson, 2025.

About the Author:

David J. Thompson was a board member of Co-opportunity and Associated Cooperatives in the 1970s and one of the earliest supporters of the NCB. In 1975, he was appointed by NCBA to be co-chair of the California bank effort with Don Rothenberg. David was the first person from the cooperative sector to work for the NCB in Washington, DC, and the #7 overall employee of the NCB.

David created a synopsis for the book by Jay Richter. “Where Credit Was Due; The Creation of the National Consumer Cooperative Bank." David became the Director of Strategic Planning, interim head of the Office of Self-Help and then Regional Director of NCB’s Western Region, covering 11 Western states. He left NCB to become Vice President of the Western Region of the National Cooperative Business Association and NCBA’s Director of International Relations.

David has written three books on cooperatives, and over 400 articles about cooperatives. He was inducted into the Cooperative Hall of Fame in 2010.